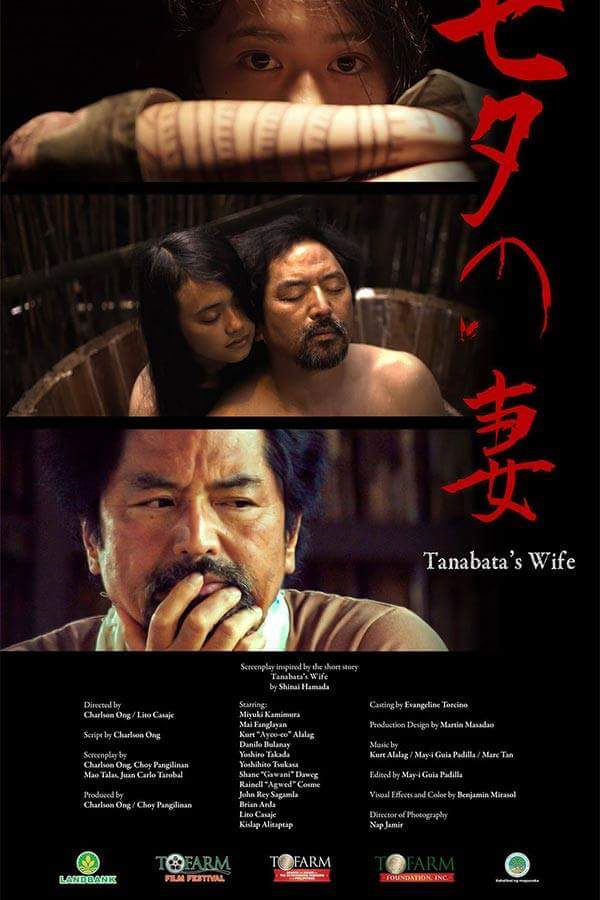

REVIEW: Tanabata’s Wife, a collaboration of genius and ingenuity

Tanabata’s Wife is based from Sinai Hamada’s short story that was written in 1932. The writer-director, Charles Ong, felt that the story has to be presented in the cinema.

Incidentally, Ong who is an award-winning literary artist re-invents himself into a cinema artist.

Amid the dark dreary weather, the narrative unfolds with a lone man playing his flute – enmeshed in his lonely self-imposed solititude – immersed in the muddied surroundings.

While the gray rain outpours, the wind musicality subtly resonates around; thus, a cacophony of organic sounds, flute playing, and even the silent mourning of a man speak.

Deserving credit to a newly discovered, Kurt Lumbag Alalag, essays his original musical design.

A glowing revelation shows a fledgling performer from a far-flunged highlands, Mai Fanglayan, whose demeanor likened to incandescent candle light is loved by the camera – gradualy yet steadily – turns into an thespian expert.

The light and shadows of the scenes as well as the grouping, framing and enclosing of objects and peoples inside the “stagy-dwelling” presents a claustrophobic nature of emaciation to the inhabitants – resonating the limitation of opportunities.

Utilizing the variating darkened tones to blackened images to grayed sepias in order to express the escalating and decreasing emotions and states of the consciousness among the character is mesmerizing.

In concerted efforts, the triad of directors collaborate their genius and ingenuity in every scene. In a classical interior arrangement of the dwelling, the husband and wife, facing each other over a low-leveled table, are posted several times before a window; while the scene opens and closes like a sliding door – a cinema technique that Yasujiro Ozu was known for.

When the wife runs away with her sibling and elopes with her lover, the transition of time essays in an effortless and streamlined phase by phase as they change in the physicality.

Further, even in the stillness of the surroundings, the grayed fog-filled images seem to move – inward or outward – as if pushing and pulling the pain and loneliness.

In the canopy of rain of quiet desolation and departing abandonment, the objects, though subtle, collapse and assemble; thus, reflect the painful separation of the characters as well as their efforts trying to harmonize their unresolved differences.

These chaos and challenges appear to reflect the constant motions among the scenes of Akira Kurosawa.

Early on and onwards, the directorial style and treatment present themselves before the hypnotized audience. At the end, they are captivated, unable to extend their responses yet able to gleam illumination over their own states.